Knowledge of diatonic chords is useful for songwriters, improvisors, and anyone else interested in how music works. On this page you'll find out what diatonic chords are and how to use them.

Also included is a list of the diatonic triads and seventh chords in every major key.

Page Index

- What are diatonic chords?

- Why are diatonic chords important?

- Diatonic Triads

- Diatonic Chord Chart

- The Diatonic Triads of Every Key

- Diatonic Triad Theory

- The Diatonic Seventh Chords of Every Key

- Using Diatonic Chords to Improve your Songwriting

Related Pages on Guitar Command

What Are Diatonic Chords?

Diatonic chords are the chords that can be made from the notes of a particular scale. For example, chords made using the notes of a C major scale are said to be diatonic to C major.

The predominant scale in a piece of music generally dictates what key the music is in. Therefore, diatonic chords can also be said to be the chords that belong to a certain key.

For example, a melody in the key of C major uses the notes of a C major scale. Typically, it would be harmonized with chords that were (mostly) diatonic to the key of C major; i.e. chords built from the notes of a C major scale.

The notes in a C major scale are: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, as shown below:

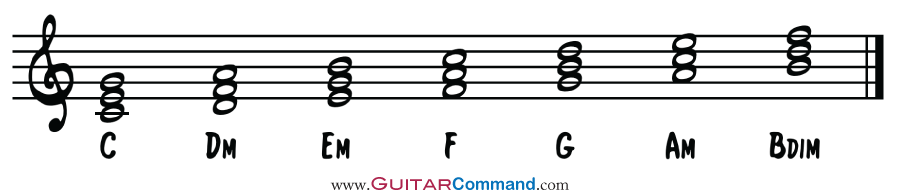

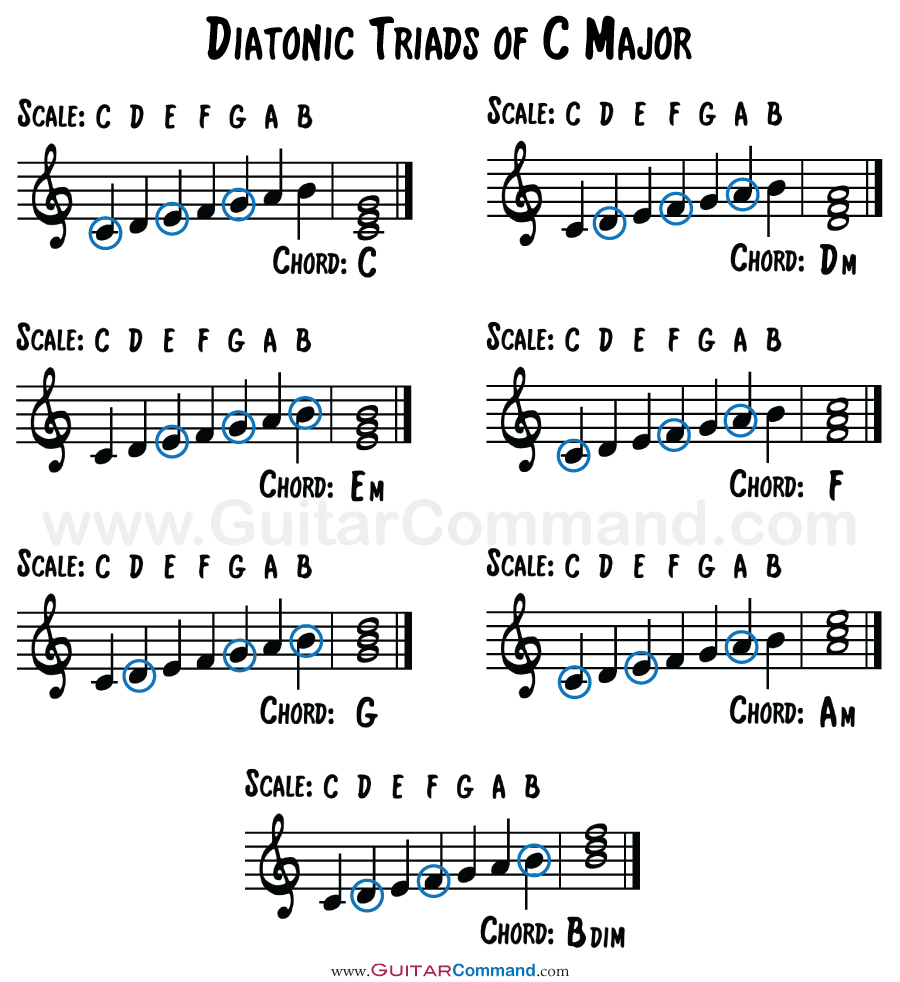

The diatonic triad chords of the key of C major are built from the notes of the C major scale, as shown below:

(When talking about diatonic chords, it is usually the triads built from a scale that are being discussed.)

Notes

Not all of the chords used to harmonize a melody have to be diatonic; non-diatonic, or 'chromatic', chords can also be used to bring additional color to an arrangement.

Music can change key. This means a new scale being used for the melody, and the new melody would therefore be harmonized with a new set of diatonic (and chromatic) chords.

Two different keys can have chords that are diatonic to both. For example, the chord of F major is diatonic to the keys of both C major and F major. (In fact, every major triad is diatonic to three keys).

Chords can be diatonic to one key and chromatic to the other. For example the chord of G major is diatonic to the key of C major but not to F major. (This is because an F major scale contains a Bb, therefore the triad built on the G is a G minor. See the 'The Diatonic Triads Of All Major Keys' section further down the page for more info.)

Why Are Diatonic Chords Important?

Knowledge of diatonic chords is useful both in songwriting and in improvising. In songwriting, knowing which chords belong to which key, and how they relate to the chords of other keys, can help you come up with new chord progressions and melodies.

Being able to tell which key you're in while improvising is an important skill. This is especially true in music that changes key frequently, such as jazz and complex rock and pop songs.

If you know the current key of the music you're improvising over, then you'll be able to select a suitable scale to use.

Knowledge of diatonic chords is an essential part of traditional music theory and classical harmony.

On this page, we'll examine the diatonic triads and diatonic seventh chords of every major scale.

We won't cover minor keys on this page; they're slightly trickier because there are more of them, and one, the melodic minor, uses different notes when descending than it does when ascending, giving it even more diatonic chords.

Diatonic Chords - Triads

As we've seen, diatonic chords are the chords that can be made from the notes of a particular scale. Therefore, chords diatonic to a C major scale are built from the seven notes of that scale, namely C, D, E, F, G, A, B.

We'll start by looking at diatonic triad chords, which contain three notes each. (Further down the page we'll discuss diatonic seventh chords.)

There are seven possible diatonic triads using the notes of a major scale; each note of the major scale becomes the root note of one of these chords.

The diatonic triads of a C major scale are C major, D minor, E minor, F major, G major, A minor and B diminished:

Diatonic Triads Chart

D Major Diatonic Chords

In a D major scale, the diatonic triads are D major, E minor, F# minor, G major, A major, B minor and C# diminished.

Notice that the order of the type of diatonic triads does not change, only the root notes. The order of the diatonic chord triads of a major scale is:

1. Major

2. Minor

3. Minor

4. Major

5. Major

6. Minor

7. Diminished.

The following diagrams will help to explain this:

Diatonic Triads - All Major Keys

Below is a chart showing all of the diatonic triads in each major key:

Diatonic Triad Theory

Triad chords contain three notes, the outer two of which are a fifth (perfect, diminished or augmented) apart. There are four kinds of triad: major, minor, diminished and augmented.

The interval between the first and second notes is a major third in major and augmented triads and a minor third in minor and diminished triads. The interval between the second and third notes is a minor third in major and diminished triads and a major third in minor and augmented triads.

Triads can also be inverted, which means that the third or fifth becomes the lowest note of the chord, rather than the root.

In first inversion, the third is the lowest note. In second inversion, the fifth is the lowest note. The diagram below shows a C major triad in root position, first inversion and second inversion.

Diatonic Seventh Chords

The triad built from the fifth degree of the scale (i.e. G in a C major scale) is often extended to include the seventh note. This produces a dominant seventh chord, which is an important chord harmonically as it creates a strong pull back to the root triad.

The other diatonic triads can also be extended in this manner in order to create diatonic seventh chords. These chords are often used to harmonize melodies in jazz.

In a major scale, the order of diatonic seventh chords is:

1. Major 7th

2. Minor 7th

3. Minor 7th

4. Major 7th

5. Dominant 7th

6. Minor 7th

7. Half-Diminished 7th (Minor 7th Flat 5)

Diatonic Seventh Chords In Every Key

Using Diatonic Chords In Songwriting

You don't need to know about diatonic chord theory in order to write a good song, but even a passing knowledge of the chords present in different keys can help you to both create melodies and harmonize songs more effectively.

If you've come up with a good melody, perhaps by jamming over chords with lyrics you have already written, then you can try harmonizing it with diatonic chords.

For example, suppose that you have written a melody in C major over a repeated C to F chord progression. You could, at various points in the song, try playing an Am in place of a C chord, or a Dm in place of the F.

Both of these minor chords are diatonic to the scale of C, and their inclusion may add another dimension to the music.

You could also experiment with the diatonic 7th versions of the chords; this is particularly effective if you want a 'jazzy' sound.

These ideas may or may not fit with the song, but knowing diatonic chords gives you some useful tools to experiment with, and may help you to find that extra something that makes a good song into a great one.

More Songwriting Ideas

You could also try adding some non-diatonic chords into your songs. Use chords that contain the notes of your melody. For example, if your song is in the key of C major, and your melody note is an E, try playing an A major chord underneath it.

The A chord isn't diatonic (there isn't a C sharp in a C major scale), but you may find that your song is suddenly given a harmonic twist that you hadn't previously considered.

A technique used in Baroque times that is still relevant today is to find a chord common to both the key you're currently in and another key. This chord can be used as a 'pivot' to prepare the listener for a key change into the new key (perhaps from a verse into a chorus).

As you experiment, you'll begin to find new ways of harmonizing your songs. Use the charts on this page to experiment with diatonic chords. Just having a little bit of music theory under your belt could mean the difference between a hit and a miss!

If you have any thoughts or questions then feel free to add a comment below; we'd be happy to help!

Can you explain the theory behind changing the 2nd chord (subdominant) in a Major scale to a dominant? For example: key G-major starting with the 4th, the progression – C A7 G G7 (song example Sweet Virginia).

Am I wrong thinking the key is G-major?

I’m having no luck finding an answer.

Thanks.

Hi,

Great question.

The chord progression you mention is a good example of how the inclusion of a non-diatonic chord or chords can add colour to a chord progression.

You’re correct; the key is G major, but both the A7 and G7 chords are non-diatonic, giving the progression a slightly ambiguous sound.

Making the ii chord (we think you mean the supertonic rather than the subdominant?) a dominant seventh, rather than a minor chord, suggests that the progression is modulating to D major (or minor), but the following chord (the G) is actually the I chord. (Try playing the progression with an Am (which is diatonic), rather than an A7 – it sounds somewhat less colourful.)

The last chord of the progression is a G7, suggesting that the progression is in C, rather than G. However, in this case the G7 is used to introduce the C chord and therefore bring the progression back to the start, rather than changing the key to C.

We hope this helps.

Regards,

The Guitar Command Team

This is awesome because I play bass and some 25 years ago I had the good fortune to take lessons with an awesome jazz guitarist named Charlie Robinson who got me going on theory. My other bandmates thought it was a waste of time by knowing something as basic as what a chords relative minor is by using the sixth note of the scale works.

One thing I can’t wrap my thick scale around is how is their a Cb instead of it being a B? In the circle of fifths and the flats being BEADGC?

They always add up to “the rule of 7”.

C = 0 sharps/flats

Cb = 7 flats

C# = 7 sharps

G = 1 sharp

Gb = 6 flats

D = 2 sharps

Db = 5 flats

And so on…